Eldercare - Resources

Finding Medicare: A Real Life Experience

Can You Play the Moonlight Sonata While Eating a Ham Sandwich

Learning the Medicare structure is not difficult; it is easier than mastering, say, a recognizable playing of the Moonlight Sonata, but more difficult than the construction of a deli-quality ham and cheese sandwich. In any case, a person will tend to become proficient with the Medicare structure when a lack of said proficiency begins costing that person money.

What To Expect

As a person approaches age sixty-five, his or her mailbox becomes inundated with large envelopes from insurance providers, advocate organizations, prior employers, present employers, the federal government, and any number of individuals and organizations that can smell money. Separating the advertising from the objective information presents a challenge. And the nomenclature of Medicare does not flow logically, but rather spreads itself out like the haphazard additions to an old farm house.

Resources

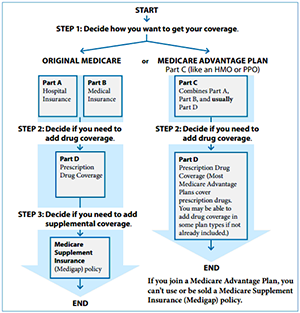

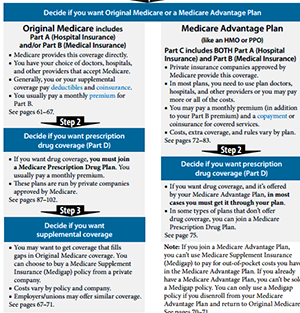

The Medicare.gov website makes a good attempt to explain the structure of Medicare to a broad and varied audience. Like many comprehensive websites, however, this one is a maze that requires numerous clicks to find the information that an individual might need. For beginners, the far right tab in the tool bar menu titled “Forms, Help, & Resources” accesses the “Medicare & You” 2014 Handbook through the “Publications” prompt. As a featured publication, it can be downloaded. It takes about forty-five minutes to scan through the publication, and a few well-constructed graphics go a long way toward presenting how Parts A, B, C, D, and Medigap coverage interface with each other.

The first graphic is on page 16. This graphic shows how Part A and Part B are the basis of the system, how Part D covers prescription drugs, and how the Part C terminology sets it apart as an alternative to Parts A and B designating Part C as a “Medicare Advantage Plan.” It also shows where the Medigap policies fit into the schematic as filling the “gap” between the traditional Parts A and B coverage and what the individual must pay out-of-pocket. Page 59 presents a graphic step-by-step approach to the decisions a person needs to make to obtain his or her coverages.

Murky Waters

The fact that Medigap (Supplemental) Plans use an alphabetic code for comparison and marketing purposes further clouds the water for those beginning their search. The A through N designations of the Medigap alternatives are not related to the Parts A, B, C, and D of the Medicare plans. Page 69 of the “Medicare and You” publication shows a graphic representation of the Medigap plans in an apples-to-apples comparison format.

The Medicare.gov site explains the structure of Medicare in various formats. But one can find the same information on the web site of most any insurer that offers Medicare coverage. USAA, for example, provides some Medicare coverage, and their site walks the viewer through this same basic structure.

And For The Final Act...

Knowing the structure and the step-by-step process, however, is only the humble beginning of a true search designed to meet each person’s insurance needs. The number of alternatives and the various costs are mind-boggling. This is where each person has to look carefully at his or her own medical and prescription drug requirements. And this is where a person might well make a hasty decision that could sting the pocketbook significantly. And while this process might well be harder than the playing of the Moonlight Sonata, if this search is conducted well, the individual will be rewarded by being able to keep the piano tuned while he or she enjoys deli-quality sandwiches at will and at leisure.

The Choice to Stay in Their Own Home, Where They Want to Be

A few western cultures still respect their elders. Italy is one. And the enterprising Italians have found a way to serve their elders and cut costs, too.

A few western cultures still respect their elders. Italy is one. And the enterprising Italians have found a way to serve their elders and cut costs, too.

Bolzano, Italy expects to realize, "30% savings in assistance and care" by adapting proven technology to help meet growing community service needs in eldercare. According to one official,"... we expect to satisfy our growing (eldercare) need with the same number of people (support staff) as before." Most importantly, these technological applications allow, "... (the elderly) the choice to stay in their own home where they want to be."

Click on the image above to view an excellent video about Bolzano and read the Huffington Post article: "Solutions for an Aging Population".

Knowing, Helping Hands

I often sit and chat with my 85-year-old neighbor Bev, and recently she’s been filling me in on the details of her life. Both heartbreaking and inspiring, it’s a story I won’t soon forget.

Bev and her husband have overcome some truly devastating challenges, from fertility struggles to substance abuse. Her husband was recently diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease, and she says that after 50 years together, coping with the necessary changes to her husband’s care, her home, and her life overall has been a lonely process.

I decided to reach out to other seniors who might be dealing with similar problems the best way I know how: I put together a collection of resources in the hopes of showing them how much support they truly have. I thought it would be a helpful addition to your website:

Aging at Home: Common Problems and Solutions

How Seniors are Designing Social Support Networks

The Ultimate Guide to Home Accommodations for Persons with Disabilities

The Benefits of Emotional Support Animals

Guide to Addiction Prevention for Seniors

Finding a Family: Discovering Your Queer Community When You’re 65

Dental Care Tips for Caregivers

Recognizing and Treating Depression: A Guide for the Elderly & Their Caregivers

Thank you for your time and help in supporting seniors everywhere!

Sincerely,

Jasmine

Jasmine Dyoco

j.dyoco@educatorlabs.org | http://educatorlabs.org/

2054 Kildaire Farm Road #204 | Cary, NC | 27518

1. If you're like most Boomers you know that you don't know — especially when it comes to eldercare. However, one thing you did learn in college, though, was that learning is forever.

You can learn much, much more about eldercare from those who really understand the challenges you are confronting now that you are taking care of your mom, dad, wife, husband or friend. But, sadly, there are few medical professionals who really understand the needs of an eldercare caregiver.

So, where to go?

We recommend you visit with Teepa Snow. “Hands down”, we feel that Teepa Snow is the very best eldercare-informed professional available today. Not only is Ms. Snow an internationally recognized dementia expert, but she knows how to communicate. Go to her website; attend one of her seminars; but, most importantly, right now, watch her videos for help. Your loved one will thank you. And, you will thank Teepa Snow for helping you.

Here's an example from one of her videos: Teepa Snow - Making Visits Valuable - Part 4: It Starts With You

2.You will find Paula Span's blog, The New Old Age (The New York Times) interesting and helpful, go here: http://newoldage.blogs.nytimes.com/

A current article, written by Judith Graham, is exceptinally illuminating: "Assisted Living vs. Hospice: Who’s in Charge?" Download PDF

Another, "Struggling With an Abusive Aging Parent", is equally important. Download PDF

Here's the description of the blog: "Thanks to the marvels of medical science, our parents are living longer than ever before. Adults over age 80 are the fastest growing segment of the population; most will spend years dependent on others for the most basic needs. That burden falls to their baby boomer children. In The New Old Age, Paula Span and other contributors explore this unprecedented intergenerational challenge."

3. It is likely that you have some time left. So, talk with your elder (s) and learn about his / her life experiences while yiou still can. We guarantee you will charish the moments later when mom and dad have passed.

4. You may discover www.payingforseniorcare.com to be one of the most helpful eldercare resources on the net. The website owner, the American Elder Care Research Organization, has also created a excellent tool which may also help you — the Eldercare Financial Resource Locator.

Established in 2007, the organization’s mission is: "to assist individuals in the planning and implementing of long-term senior care." It was developed "as a result of the founders’ personal experience navigating the maze of program eligibility requirements... (by) Carol Guerrero, an attorney specializing in estate planning and other legal issues of seniors, and Alex Guerrero, a website developer (who) drew from the expertise of other immediate family members (in medicine, law and research) combining their experience and skills to create the PayingForSeniorCare.com website."

According to their website: "During its first three years, our organization was funded entirely by donation. By 2011, however, we began to receive a small referral fee from eldercare service providers if a visitor to our website engaged with their service. Through this arrangement we are now able to sustain operations and strive towards our mission without other financial assistance or the use of display advertising on the website."

5. Visit the Legacy Project http://legacyproject.human.cornell.edu created by Dr. Karl Pillemer, a professor of human development in the College of Human Ecology at Cornell University, and Professor of Gerontology in Medicine at the Weill Cornell Medical College.

"The Legacy Project has systematically collected practical advice from over 1500 older Americans who have lived through extraordinary experiences and historical events. They offer tips on surviving and thriving despite the challenges we all encounter."

Surviving Your Hospital Stay

95-year-old Offers 10 Tips for Surviving Your U.S. Hospital Stay

Grosse Ile, MI - Take it from a proven hospital survivor – you need lots of help to survive your U.S. hospital stay.

Recently, Trula Ryan, 95, came home from her 85-day-stint at two metro Detroit hospitals. She is an uncontested survivor and can attest to the fact that the very best tip is, “Stay away from the hospital unless you have no other option and you absolutely must go.”

Recently, Trula Ryan, 95, came home from her 85-day-stint at two metro Detroit hospitals. She is an uncontested survivor and can attest to the fact that the very best tip is, “Stay away from the hospital unless you have no other option and you absolutely must go.”

Following a trip to emergency and hip surgery, Ms. Ryan encountered nearly every medical complication, as well as nearly every prejudice which American culture can dish out on her bumpy road to recovery, including: “You’re 95, you know! What do you expect at your age!” And, Even if you survive breathing with a vent, nobody comes off of them and you will end up on a shelf and have no life anyway.” Plus, Is it really your decision to live or can’t your family just let you go?”

Still, she beat the odds and the naysayers. Today, she’s at home, enjoying watching her beloved Detroit Tigers and giving everyone she sees her trademarked, “Two Thumbs Up!”

Here are Trula’s 10 Tips for Surviving your hospital stay:

- Empower someone you trust and who loves you to be your patient advocate.

- Each day, especially Fridays, Saturdays, Sundays and holidays, at the beginning of every shift, your patient advocate must meet and be confident in your assigned nurse. Follow this practice until you leave the hospital.

- Move to a room, as close to the nurses’ station as you can be. If the room is semi-private, ask for the bed closest to the entry door.

- Make sure your patient advocate understands which medications your doctor has ordered for you as well as how much of each medication you are to receive.

- Make absolutely certain that your patient advocate ensures that your nurse correctly administers your medications as your doctor has ordered.

- Do not submit to any procedure unless you understand that your doctor has ordered it for you and you have agreed to have it done.

- Closely observe the nursing team and make certain that they wash their hands and use clean gloves; do not use suction tubes which have fallen onto the floor or onto your bed; and maintain sterile technique when required, e.g. when changing a PICC line (peripherally inserted central catheter) dressing.

- Question everything and ask your questions in three different ways.

- Ask what are the known side effects of every medication and procedure.

- Research everything until you feel comfortable that you understand.

Perhaps, most importantly, says Trula, “Just never give up, no matter who says you can’t make it, because you can!”

Trula Update

At the end of March 2014, Trula came home from the hospital after a seven-day stay. Her doctor suspected pneumonia, but it turned out she had a serious case of bronchitis. Previously, she was hospitalized for serious loss of blood due to taking Coumadin, the blood thinner. Prior to that stay, she was hospitalized for a bladder infection.

Trula has gone through a lot due to her health complications but even more due to hospital-related errors. Following each discharge, she arrived home physically weaker than when she left but still determined to keep going forward.

She made it past her 96th birthday, still THE Detroit Tigers fan to the end. She passed 30 Sept 2014.

How Many Die From Medical Mistakes in U.S. Hospitals?

by Marshall Allen, ProPublica, 19 Sept 2013

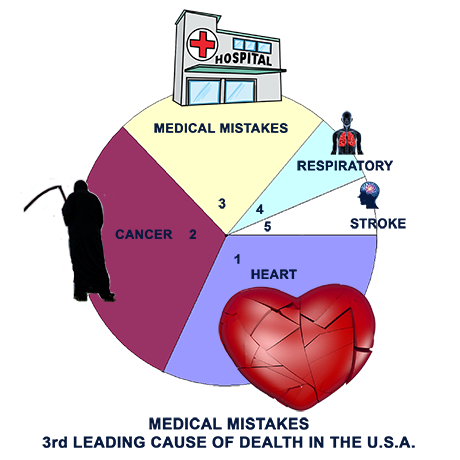

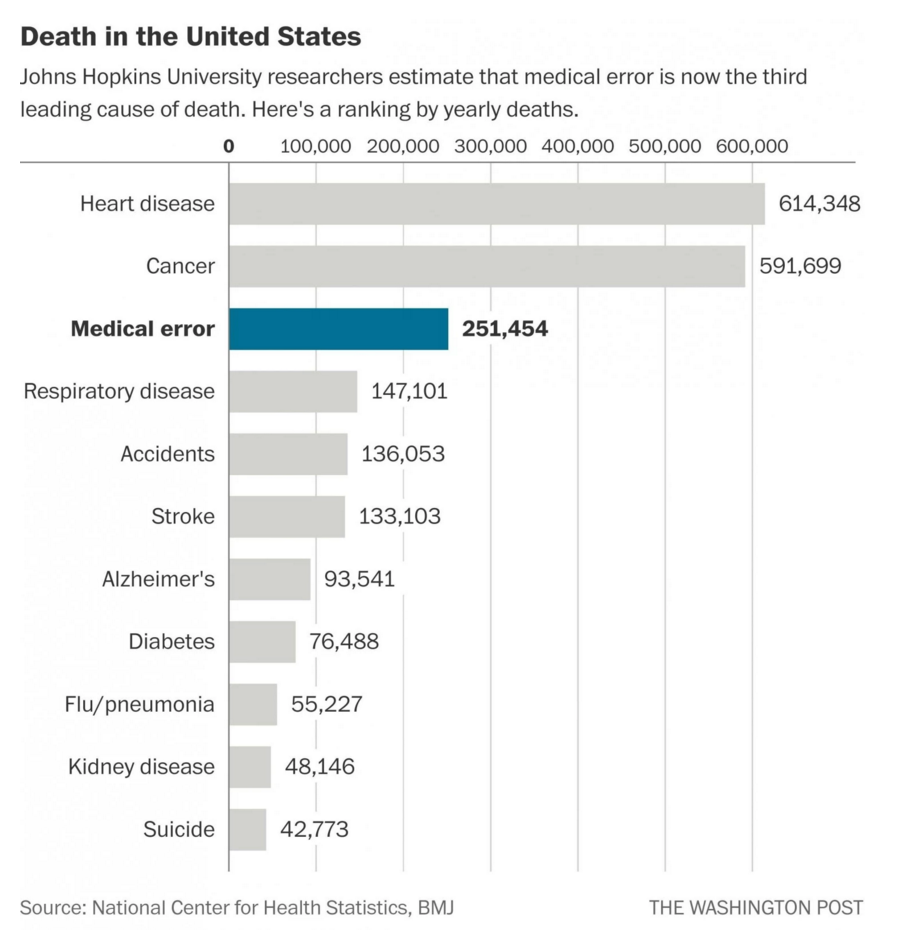

A recent study published by the Journal of Patient Safety says the number of deaths resulting from medical mistakes in U.S. hospitals may be between 210,000 and 440,000 patients each year.

“That would make medical errors the third-leading cause of death in America, behind heart disease, which is the first, and cancer, which is second.”

One wonders, what happens to this comparison if the "medical mistakes" category were expanded to include "nursing homes" and other extended care institutions? I will bet that the "medical mistakes" category will move up on the list of leading causes of death in the U.S. (ed)

Go here for the complete story or download a PDF version here.

Medical Mistakes Updated 2016

Verification of the Medical Mistakes data was recently published in two Washington Post articles and two medical journals. Here’s the story:

"It boils down to people dying from the care that they receive rather than the disease for which they are seeing care,” explained Dr. Martin Makary, a professor of surgery at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine who led the research which was published a couple of days ago in the BMJ (formerly, The British Medical Journal). (1)

And…in a paper recently published in JAMA Surgery (Journal of the American Medical Association), researchers said that they discovered: “…a mere seven procedures accounted for approximately 80 percent of all admissions, deaths, complications and inpatient costs related to emergency surgeries.”

Continuing… “The seven dangerous and costly procedures are mostly related to the organs of the digestive system: removing part of the colon, small-bowel resection, removing the gallbladder, operations related to peptic ulcer disease, removing abdominal adhesions, appendectomy and other operations to open the abdomen.” (2)

So, what can you do to protect yourself from becoming an additional bit of datum in a future research medical error report? Answer… Do Not Go to the Hospital for Any Reason!!!

O.K. I know that at some point you may wake up in the emergency room. And / or knowing that there is next to nothing you can do to protect yourself from errors made during surgical procedures. Then, if you must be in the hospital, see the previous story: Here are Trula’s 10 Tips for Surviving your hospital stay.

1. Researchers: Medical errors now third leading cause of death in United States, Ariana Eunjung Cha, Washington Post, 3 May 2016.

2. ‘Looming catastrophe’: These 7 emergency surgeries account for 80 percent of deaths and costs, Ariana Eunjung Cha, Washington Post, 27 Apr 2016.

How Mom's Death Changed My Thinking About End-of-Life Care

Charles Ornstein with his mother Harriet Ornstein on his wedding day, weeks after she was mugged in a parking lot and knocked to the pavement with a broken nose. (Randall Stewart, Photo courtesy of Charles Ornstein)

by Charles Ornstein, ProPublica, 28 Feb 2013

This story was co-published with The Washington Post.

My father, sister and I sat in the near-empty Chinese restaurant, picking at our plates, unable to avoid the question that we'd gathered to discuss: When was it time to let Mom die?

It had been a grueling day at the hospital, watching — praying — for any sign that my mother would emerge from her coma. Three days earlier she'd been admitted for nausea; she had a nasty cough and was having trouble keeping food down. But while a nurse tried to insert a nasogastric tube, her heart stopped. She required CPR for nine minutes. Even before I flew into town, a ventilator was breathing for her, and intravenous medication was keeping her blood pressure steady. Hour after hour, my father, my sister and I tried talking to her, playing her favorite songs, encouraging her to squeeze our hands or open her eyes.

Doctors couldn't tell us exactly what had gone wrong, but the prognosis was grim, and they suggested that we consider removing her from the breathing machine. And so, that January evening, we drove to a nearby restaurant in suburban Detroit for an inevitable family meeting.

My father and sister looked to me for my thoughts. In our family, after all, I'm the go-to guy for all things medical. I've been a health-care reporter for 15 years: at the Dallas Morning News, the Los Angeles Times and now ProPublica. And since I have a relatively good grasp on America's complex health-care system, I was the one to help my parents sign up for their Medicare drug plans, research new diagnoses and question doctors about their recommended treatments.

In this situation, like so many before, I was expected to have some answers. Yet none of my years of reporting had prepared me for this moment, this decision. In fact, I began to question some of my assumptions about the health-care system.

I've long observed, and sometimes chronicled, the nasty policy battles surrounding end-of-life care. And like many health journalists, I rolled my eyes when I heard the phrase "death panels" used to describe a 2009 congressional proposal that would have allowed Medicare to reimburse physicians who provided counseling to patients about living wills and advance directives. The frenzy, whipped up by conservative politicians and talk show hosts, forced the authors of the Affordable Care Act to strip out that provision before the bill became law.

Politics aside, I've always thought that the high cost of end-of-life care is an issue worthy of discussion. About a quarter of Medicare payments are spent in the last year of life, according to recent estimates. And the degree of care provided to patients in that last year 2014 how many doctors they see, the number of intensive-care hospitalizations 2014 varies dramatically across states and even within states, according to the authoritative Dartmouth Atlas.

Studies show that this care is often futile. It doesn't always prolong lives, and it doesn't always reflect what patients want.

In an article I wrote for the Los Angeles Times in 2005, I quoted a doctor saying: "There's always one more treatment, there's always one more, 'Why don't we try that?' ... But we have to realize what the goals of that patient are, which is not to be in an intensive-care unit attached to tubes with no chance of really recovering."

That made a lot of sense at the time. But did it apply to my mom?

We knew her end-of-life wishes: She had told my dad that she didn't want to be artificially kept alive if she had no real chance of a meaningful recovery. But what was a real chance? What was a meaningful recovery? How did we know if the doctors and nurses were right? In all my reporting, I'd never realized how little the costs to the broader health-care system matter to the family of a patient. When that patient was my mother, what mattered was that we had to live with whatever decision we made. And we wouldn't get a chance to make it twice.

As my mom lay in the ICU, there was no question that her brain function was worrisome. In the hours after she was revived, she had convulsions, known as myoclonus, which can happen if the brain lacks oxygen. After that, she lay still. When the neurologist pricked her with a safety pin, she didn't respond. When he touched her corneas, they didn't reflexively move.

I began checking the medical literature, much like I do as a reporter. I didn't find anything encouraging. Studies show that after 72 hours in a coma caused by a lack of oxygen, a patient's odds of recovery are slim to none. I asked my writing partner in New York to do additional research. She, too, found nothing that would offer much hope.

But couldn't my mom beat the odds? Harriet Ornstein was a feisty woman. At age 70, she had overcome adversity many times before. In 2002, weeks before my wedding, she was mugged in a parking lot and knocked to the pavement with a broken nose. But she was there to walk me down the aisle 2014 black eyes covered by makeup. She had Parkinson's disease for a decade, and in 2010 she suffered a closed head injury when a car backed into her as she walked down a handicapped ramp at the drugstore. Mom persevered, continuing rehabilitation and working to lead as normal a life as possible. Might she not fight through this as well?

Truth be told, I was already somewhat skeptical about physician predictions. Just last summer, my dad's heart stopped, and it took more than 10 minutes of CPR to revive him. Doctors and nurses said a full neurological recovery was unlikely. They asked about his end-of-life choices. Mom and I stayed up late talking about life without him and discussing the logistics of his funeral. But despite it all, he rebounded. He was home within weeks, back to his old self. I came away appreciative of the power of modern medicine but questioning why everyone had been so confident that he would die.

Also weighing on me was another story I wrote for the Los Angeles Times, about a patient who had wrongly been declared brain-dead by two doctors. The patient's family was being urged to discontinue life support and allow an organ-donation team to come in. But a nursing supervisor's examination found that the 47-year-old man displayed a strong gag-and-cough reflex and slightly moved his head, all inconsistent with brain death. A neurosurgeon confirmed her findings.

No one was suggesting that my mom was brain-dead, but the medical assessments offered no hint of encouragement. What if they were off-base, too?

Over dinner at the Chinese restaurant, we made a pact: We wouldn't rush to a decision. We would seek an additional medical opinion. But if the tests looked bad 2014 I would ask to read the actual clinical reports 2014 we would discontinue aggressive care.

A neurologist recommended by a family acquaintance came in the next morning. After conducting a thorough exam, this doctor wasn't optimistic, either, but she said two additional tests could be done if we still had doubts.

If more tests could be done, my dad reasoned, we should do them. My sister and I agreed.

On Friday morning, the final test came back. It was bad news. In a sterile hospital conference room, a neurologist laid out our options: We could move my mom to the hospice unit and have breathing and feeding tubes inserted. Or we could disconnect the ventilator.

We decided it was time to honor my mom's wishes. We cried as nurses unhooked her that afternoon. The hospital staff said it was unlikely that she would breathe on her own, but she did for several hours. She died peacefully, on her own terms, late that night 2014 my dad, my sister and I by her side.

I don't think anyone can ever feel comfortable about such a decision, and being a health reporter compounded my doubts.

I was fairly confident that we did what my mom would have wanted. But a week later, when I was back in New York and had some emotional distance, I wondered how our thinking and behavior squared with what I'd written as a reporter. Did we waste resources while trying to decide what to do for those two extra days? If every family did what we did, two days multiplied by thousands of patients would add up to millions of dollars.

Curious how experts would view it, I called Elliott S. Fisher. I've long respected Fisher, a professor of medicine at Dartmouth and a leader of the Dartmouth Atlas. The Atlas was the first to identify McAllen, Texas, subject of a memorable 2009 piece in the New Yorker by Atul Gawande, for its seemingly out-of-control Medicare spending.

I asked Fisher: Did he consider what my family did a waste of money?

No, he said. And he wouldn't have found fault with us if we decided to keep my mom on a ventilator for another week or two, although he said my description of her neurological exams and test results sounded pessimistic.

"You never need to rush the decision-making," he told me. "It should always be about making the right decision for the patient and the family. ... We have plenty of money in the U.S. health-care system to make sure that we're supporting families in coming to a decision that they can all feel good about. I feel very strongly about that."

Plenty of money? How did this mesh with his view that too much money is spent on care at the end of life? He said his concern is more about situations in which end-of-life wishes aren't known and cases where doctors push treatments for terminal illnesses that are clearly futile and that may prolong suffering.

"I don't think the best care possible always means keeping people alive or always doing the most aggressive cancer chemotherapy," he said, "when the evidence would say there is virtually no chance for this particular agent to make a difference for this patient."

I left the conversation agreeing with Fisher's reasoning but believing that it's much harder in practice than it is in theory. You can know somebody's wishes and still be confused about the appropriate thing to do.

The past few weeks have been the most difficult of my life. I hope what I learned will make me a better, more compassionate journalist. Most of all, I will always remember that behind the debate about costs and end-of-life care, there are real families struggling with real decisions.

Senior reporter Charles Ornstein is board president of the Association of Health Care Journalists and can be reached at charles.ornstein@propublica.org. Go here to download PDF version of this article.

Our Plan

Our Plan